On the night of January 11, 1989, President Ronald Reagan gave his farewell address. Included in his parting remarks was an admonition for Americans to take stock in what we teach our children about our nation’s history. Reagan asked, “Are we doing a good enough job teaching our children what America is and what she represents in the long history of the world?” The president went on to highlight key moments in this nation’s history, beginning with the Pilgrims.

Who are these Pilgrims mentioned by the president? Why mention them? Why is their story important? Is it even relevant in our time, 400 years later? While there is so much to distract us from this momentous occasion, we dare not fail to give due consideration and credence to the lessons we can still learn from their lives, their mission, and their sacrifice.

We owe a wealth of gratitude to the providence of God in preserving the reliable record we have of these reformers, who left England under the scourge of religious persecution. Two primary sources, having withstood the ravages of time and man, still resolutely proclaim the firsthand account of the Pilgrims’ incredible quest for liberty: William Bradford’s Of Plimoth Plantation and George Morton’s Mourt’s Relation. Sadly, in recent times the details of these meticulous journals have been obscured or dismissed for political reasons in an attempt to erase “America’s Sacred Story.” Let us take a brief journey back in time to learn from “those of whom the world is not worthy” as their lives sing a song of truth, courage, and faith.

The Pilgrims: A People of the Book

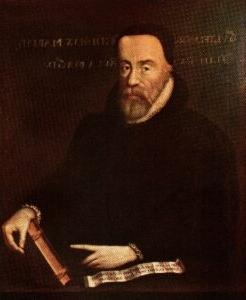

William Tyndale, who was strangled and burned at the stake in 1536 after publishing his English translation of the New Testament. In a providential twist, it was a revision of Tyndale’s work, known as the Geneva Bible (1599), that the Pilgrims carried with them to the New World in 1620.

The congregation of separatists, who met in Scrooby, England, in the early 17th century, was the product of a long line of reformers beginning notably with John Wycliffe, called the Morning Star of the Reformation. It was Wycliffe who first began translating portions of the New Testament into common English in 1382, which lit a fire that would not be quenched despite his death or his subsequent excommunication from the Church of England and the burning of his exhumed body.

Another significant individual on the Pilgrim timeline is William Tyndale, who was strangled and burned at the stake in 1536 after publishing his English translation of the New Testament. In a providential twist, it was a revision of Tyndale’s work, known as the Geneva Bible (1599), that the Pilgrims carried with them to the New World in 1620.

In his seminal journal, Bradford notes the impact of the Bible on “many in the North of England and other parts became enlightened by the word of God and had their ignorance and sins discovered unto them, and began by His grace to reform their lives and pay heed to their ways.” 2 Bradford goes to great lengths enumerating the various trials, tribulations, and persecutions the separatists endured “until by the increase of their troubles they began to see further into things by the light of the word of God.” 3 As time went on, these reformers, “whose hearts the Lord had touched with heavenly zeal for His truth, shook off this yoke of anti-Christian bondage and as the Lord’s free people joined themselves by covenant as a church, in the fellowship of the Gospel to walk in all His ways, made known or to be made known to them, according to their best endeavours, whatever it should cost them, the Lord assisting them. And that it cost them something, the ensuing history will declare.”4

Bradford provides vivid and numerous examples of their trials and tribulations, which led them to leave their native homeland for Holland because it offered more religious tolerance. The fledgling group, now in Leiden, increased as “they grew in knowledge and other gifts and graces of the spirit of God, and lived together in peace and love and holiness; and many came to them from other parts of England, so that there grew up a great congregation.”5 Bradford summarizes the effect that their spiritual enlightenment had on them, stating, “I know not but it may be spoken to the hour of God, and without prejudice to any, that such was the true piety, the humble zeal, and the fervent love, of this people, whilst they lived thus together, towards God and His ways, and the single-hearted and sincere love they had towards another, that they came as near the primitive pattern of the first churches as any other church of these later times has done.”6

To experience the full light of the Christian commitment and zeal of the Pilgrims, one must embark on a journey through the entirety of Bradford’s history. It was their commitment to God and His ways that enabled the Pilgrims to endure the dangers of their long voyage over the Atlantic Ocean, the harshness of the terrible first winter, and the starving times, without which the roots of biblical Christianity on these shores would have, perhaps, been snuffed out, along with the liberty that arises from the Gospel wherever it is deposited.

The Pilgrims: A People of Christian Character

Bradford, as second and longtime governor of the plantation, offers no illusion concerning their humanness. The Pilgrims, as we, had their struggles, faults, and failures. Yet they were remarkably resilient, forgiving, and consistent in living out their faith in word and deed. Rather than giving up in despair, they chose to take God at His word and persevere under the most difficult burdens, which only heightened as they came upon the New England shore at winter’s start in 1620.

That the severity of their plight would only grow, they scarcely could know. As Bradford recounts, the winter took a terrible toll on them, with half of their company of just over 100 dying of general sickness before spring. In the midst of this great trial, Christ shined brightest, for the few who were not sick “with great toil and at the risk of their own health, fetched wood, made fires, prepared food for the sick, made their beds, washed their infected clothes, dressed and undressed them … and all this they did willingly and cheerfully, without the least grudging, showing love to the friends and brethren; a rare example, and worthy to be remembered.”7 They even cared with great compassion and love for the sailors who had treated them so savagely on their voyage. Bradford recalled how one particularly abusive shipman recognized the contrast between the “saints and strangers,” as they were called, remarking, “You, I see now, show your love like Christians indeed to one another; but we let one another die like dogs.”8

That the severity of their plight would only grow, they scarcely could know. As Bradford recounts, the winter took a terrible toll on them, with half of their company of just over 100 dying of general sickness before spring. In the midst of this great trial, Christ shined brightest, for the few who were not sick “with great toil and at the risk of their own health, fetched wood, made fires, prepared food for the sick, made their beds, washed their infected clothes, dressed and undressed them … and all this they did willingly and cheerfully, without the least grudging, showing love to the friends and brethren; a rare example, and worthy to be remembered.”7 They even cared with great compassion and love for the sailors who had treated them so savagely on their voyage. Bradford recalled how one particularly abusive shipman recognized the contrast between the “saints and strangers,” as they were called, remarking, “You, I see now, show your love like Christians indeed to one another; but we let one another die like dogs.”8

Bradford concluded that “from these extremities the Lord in His goodness kept these His People, and in their great need preserved both their lives and their health; let His name be praised.” 9He went on to state, “God, it seems, would have all men behold and observe such mercies and works of His providence as towards His People, that they in like cases might be encouraged to depend upon God in their trials, and also bless His name when they see His goodness towards others.” 9

The Pilgrims: A People with a Vision for Liberty

The Pilgrims had a keen sense of their personal and corporate individuality. Much of the hardship they endured stemmed from their pursuit of freedom, beginning first in their conscience as manifest in their worship of God but also extending to the external spheres of government, economics, and property. Bradford addressed these areas in his narrative account of the rise of the Plimoth Colony, writing, “Both they and all the world knew that they had come here to enjoy liberty of conscience and the free use of God’s ordinances, and for that end had ventured their lives and had already passed through so much hardship; and they and their friends had borne the expense of these beginnings, which was not small.”10

For some time, the idea of self-government was rising in the consciousness of the English people. The Pilgrims saw its implications as they traversed the ocean, were blown off course, and had to make some adjustments in their expected venture. Their famous Mayflower Compact heralded the coming of a time when a new nation would coalesce around the biblical view of God, man, and government, recognizing that civil government exists for the benefit of mankind, not the other way around.

The seed of Christian self-government planted within the Compact foreshadows the principle of voluntary union seen in the Preamble to the United States Constitution. Bradford recorded its words for posterity: “by these presents solemnly and in the presence of God, and of one another, covenant and combine ourselves into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation … enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitution … as thought most meet and convenient for the just use of the Colony, unto which we promise with all due submission and obedience.”11

That individuals in a self-governing society must have control of their own destiny was not lost on the Pilgrims. As indentured servants of the Virginia Company, they had little control over their wellbeing until their years of service and payback were accomplished. However, knowing the character and nature of humanity, they embraced the biblical principle of private property and economics. It did not take long for the Pilgrims to petition a reversal of the socialistic framework foist upon them by the Merchant Adventurers of England, who funded the voyage. Bradford wrote, “The failure of this experiment of communal service, which was tried for several years, and by good and honest men proves the emptiness of the theory of Plato and other ancients, applauded by some of later times – that the taking away of private property, and the possession of it in community or commonwealth, would make a state happy and flourishing; As if they were wiser than God.”12 He continued, “Let none argue that this is due to human failing, rather than to this communistic plan of life in itself. I answer, seeing that all men have this failing in them, that God in His wisdom saw that another plan of life was fitter for them.” 13

The idea of private property was cherished by the Pilgrims, not just for their own sakes, but also in their dealings with the natives already established in that area. Bradford made reference to recompensing the Indians for the hidden supply of corn they had unknowingly stolen upon their arrival that first terrible winter. He also described the establishment of a peace treaty with the Great Sachem, Massasoit, which lasted more than 50 years, as well as the arbitration of a peace treaty between two warring tribes. The Pilgrims’ actions keep with Matthew 5:9, which states, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the sons of God.”

The Pilgrims: America’s Sacred Story

Indeed, the Pilgrim story is America’s Sacred Story. The Christian foundation of our nation is evidenced in its record. We must preserve and protect its message, for if it is destroyed or lost, we shall vanish as a free nation. What we see in America today is the result of our neglect over many decades to teach these vital principles to our children.

In 1843, John Overton Choules wrote in his preface to a reprinted history book,

In 1843, John Overton Choules wrote in his preface to a reprinted history book,

We should never forget that the prison, the scaffold, and the stake were stages in the march of civil and religious liberty which our forefathers had to travel, in order that we might attain our present freedom. … Before our children remove their religious connexions … before they leave the old paths of God’s Word … before they barter their birthright for a mess of pottage – let us place in their hands this chronicle of the glorious days of the suffering Churches, and let them know that they are the sons of the men ‘of whom the world was not worthy,’ and whose sufferings for conscience’ sake are here monumentally recorded. 14

What President Reagan opined so many years ago still applies today, perhaps even more so:

Younger parents aren’t sure that an unambivalent appreciation of America is the right thing to teach modern children. And as for those who create the popular culture, well-grounded patriotism is no longer the style. Our spirit is back, but we haven’t reinstitutionalized it. We’ve got to do a better job of getting across that America is freedom – freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of enterprise. And freedom is special and rare. It’s fragile. … I’m warning of an eradication of the American memory that could result, ultimately, in an erosion of the American spirit.

We must preserve and protect the Pilgrim’s message, for if it is destroyed or lost, we shall vanish as a free nation.

At Dayspring Christian Academy, students are taught Providential history, the view that God is actively involved in every aspect of life, telling His story throughout history for His plans and purposes. Consequently, students learn the rudiments of America’s Christian history, from the time of the Pilgrims to its founding, up to current times. Thinking and reasoning from God’s Word enables students to identify Truth and stand firm in their faith. Dayspring students delve deeply into the timeline of Christian history and arrive at the question, “How will God use me in His story?” To learn more, take a tour. Register online or call Karol Hasting at 717-285-2000.

Works Cited:

1 http://www.reaganfoundation.org/media/128652/farewell.pdf

Paget, Harold. (1909). Bradford’s history of the Plymouth settlement. Reprinted by Mantle Ministries (1988). San Antonio, TX. (All excerpts from Bradford’s journal used in this article come from this translation into more modern English.)

3Ibid

4Ibid

5Ibid

6Ibid

7Ibid

8Ibid

9Ibid

10Ibid

11Ibid

12Ibid

13Ibid

14 Hall, V. M. (2006). The Christian history of the Constitution of the United States of America. Christian Self-Government (Founders Edition, Vol. 1, pp. 183–184). San Francisco: Foundation for American Christian Education.